Personally, no travel writer has inspired me more than perpetual world traveler and self-proclaimed vagabond, Rolf Potts. Best known for his inspirational tome Vagabonding: An Uncommon Guide to the Art of Long-Term World Travel, Rolf has no doubt inspired an entire generation of contemporary travelers.

Vagabondish is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission. Read our disclosure.

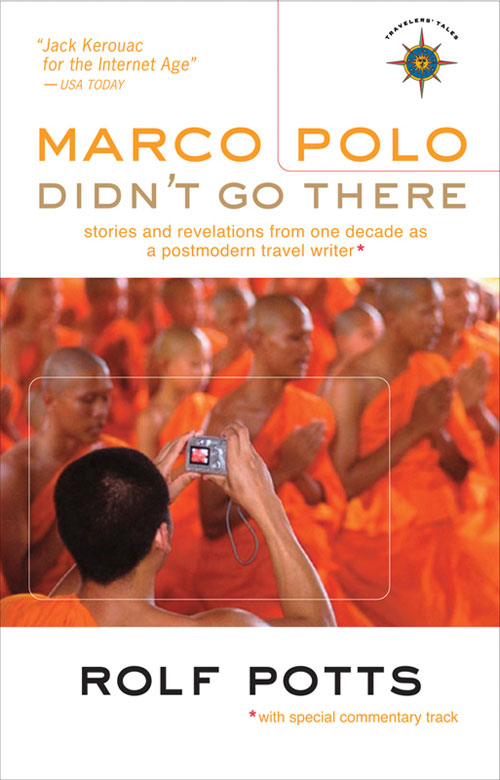

Just released this week is his latest book, Marco Polo Didn’t Go There – a collection of his funniest, boldest and most intriguing tales to date.

Vagabondish.com is among the stops on his virtual book tour and we had the privilege of sitting down for an exclusive Q&A session with Rolf.

© Rolf Potts

Your new book recounts various adventures to far-flung parts of the world, but it’s also an incisive look into life as a travel writer. What do you think about the state of contemporary travel writing?

It’s hard to speak in generalities about “contemporary travel writing,” because this term encompasses so much. There are so many different kinds of travel writing, from service articles to literary narrative to destination features. Much of it is geared toward the consumer experience and hence it’s going to be more practical than artistic in nature. In the process, a lot of it can come off sounding generic and clichéd.

Of course the generic clichés of travel writing — the overwrought language and harebrained chirpiness — have always been a part of the genre. When I teach nonfiction writing at the Paris American Academy each summer, I sometimes use On Writing Well, a classic text by William Zinsser that was written in the 1970’s. One of the chapters in this book is about capturing sense of place, and Zinsser pinpoints the travel-writing clichés that still hold true today — and probably always will hold true for certain types of consumer and destination travel articles.

All that said, I’m quite optimistic about contemporary travel writing. There are some talented people out there interpreting the postmodern travel landscape in interesting ways. It’s not that hard to find compelling, evocative travel writing out there. In addition to your better consumer travel magazines, Internet travel magazines and even blogs often publish thoughtful narrative writing — and literary journals and general interest magazines occasionally run fantastic travel essays.

I think it’s a great time to be a travel writer. Perhaps it’s not the best time to make a ton of money writing literary travel narrative, but most serious travel writers aren’t in it for the money anyhow.

You mention the creative writing workshop you teach each summer in Paris — what’s your approach to teaching writing?

One of my main goals at the writing workshop in Paris is to teach story structure, since so many beginning writers underestimate the role of structure in narrative nonfiction. I know I did when I was beginning as a writer — I thought all you had to do was write beautiful sentences in chronological order and your job was done. But that wasn’t the case. Modern audiences don’t have time for unfocused, unformed diary-like narratives — they need you to guide their reading experience. Of course the secret is inserting your story structure so deftly that it seems effortless — so that the reader doesn’t realize you had such a careful hand in forming the narrative. My new book, Marco Polo Didn’t Go There, contains endnotes after each chapter that explain how I transformed ragged, complicated real-life travel experiences into coherent, theme-driven stories. In addition to being humorous, these endnotes are meant to show how a simple travel story is rarely as simple as it might seem.

In your bio, it says that you feel somewhat at home in Bangkok, Cairo, Pusan, New Orleans, and north-central Kansas, where you have a small farmhouse near your family. Why, out of all the places in the world where you’ve been, do you feel a special kinship with these places?

I think all of these places simply captured my imagination, often in unexpected ways.

Pusan, for example, is not a very glamorous place — it’s just a big, gritty Korean port city. But it’s the place where I really cut my expatriate teeth, back when I was teaching English for a living. I learned to love Pusan, even as I had some tough and challenging experiences in adapting to life overseas. Cairo is a place that charmed me in unexpected ways, and wandering the random back-alleys of that city can be more fascinating to me than any tour of the Pyramids.

New Orleans was a place where I felt called to live for a spell, and I kept a small apartment in the French Quarter for a few months just prior to the Hurricane Katrina disaster in 2005.

Bangkok is just Bangkok — it offers endless surprises for anyone willing to be patient and put up with its vibrant chaos. There are other places where I feel at home, too, like the Latin Quarter of Paris or New York City.

My Kansas farmhouse is a kind of sanctum for me, a place where I can take a break from the road and enjoy the silence and be close to my family. It’s also a place where I can get a lot of work done — a place to slow down and be close to nature for a while. It’s off-the-beaten path in the truest sense of the word. Not many people visit Kansas in their travels, but I find new little adventures and discoveries every time I return.

Your new book shows that you’ve led a pretty adventurous life over the past 10 years. What advice might you have for a stable nine-to-five office type who is looking to add some international adventure to their life?

Simply decide to do it. It’s actually really energizing once you’ve made the decision to set out and make your dream journey, even if that journey won’t be a reality for another couple years. What might be an otherwise unremarkable stretch of two years of working in an office can actually be kind of thrilling when you know that this work is going to finance an amazing global adventure. That’s why I encourage everyone to embrace their work, even if they don’t particularly like it — fun or not, work is how you earn your freedom to make your travel dreams a reality.

Obviously there is an element of risk involved in leaving a steady lifestyle to travel the world — especially for an extended period of time. But you have to put things into perspective and realize that you’re only given so many years in life. Which will you remember best in your old age — a six-month journey across Europe and Asia, or an uninterrupted 20-year stint of working and saving for retirement? Naturally, the uncommon choice is going to be what makes your life experiences richer.

I don’t mean to knock those who choose a stable lifestyle — there are rewards inherent in that kind of life, too. But if you’ve dreamed of getting out and exploring the world at some point in life, it’s worth it to forego some stability as an existential tradeoff for that life-adventure. I have yet to hear from anyone who regrets taking that risk.

You’ve been traveling almost non-stop for years, but certainly there was a time when you were a travel novice. What might surprise readers about your early days as a traveler?

I was a late bloomer. Growing up in Kansas, smack in the middle of the USA, I was 15 years old before I ever saw the ocean. And I didn’t own a passport until I was 25. Yet just over a decade later I’ve explored six continents and I feel as comfortable in Cairo or Rio as I do in Seattle or Boston. I think this goes to show that there’s no stereotype that dictates who will and won’t travel.

As my own story proves, traveling the world is more a matter of desire and willpower than some privileged set of circumstances. I didn’t travel abroad when I was a kid, nor did I have much money growing up, but I eventually wandered my way across the world just the same. In many ways, I wrote Vagabonding as a letter to my 18 year-old self, to encourage people like me about the possibilities of travel. You don’t need tons of money to take your dream trip around the world; you just need the right attitude.

In the pages of Marco Polo Didn’t Go There, many of your most colorful adventures and misadventures come about by accident. What are some of the most shocking or unexpected moments and events you’ve experienced in all your years of travel?

Travel is one ongoing lesson in the unexpected. At its best, it surprises you with each day, and continually dispels your preconceptions.

After you’ve traveled awhile, you have new standards for what is and is not shocking. When I first went to India, I was continually amazed and exhausted by all the sensory input — you could literally see the most amazing sight of your life within hours of having seen the most disgusting sight of your life. After four months in India I got used to these aesthetic extremes — deformed beggars amid magnificent landscapes, for example — and it became somewhat normal. Then I went home to the U.S. and was shocked by, say, how big the food portions were at restaurants, or how quiet American cities can be by comparison. So travel recalibrates one’s sense of shock, to the point that a Pushkar market can be a shock if you’ve just flown in from Wichita, but a Wichita Wal-Mart can be an equal shock if you’ve just spent four months wandering Rajasthan.

As for the unexpected, I’d say that travel is one ongoing lesson in the unexpected. At its best, it surprises you with each day, and continually dispels your preconceptions. That’s part of what makes travel so addictive, I think — you’re never quite sure what you’re going to get, and this allows you the opportunity to be amazed again and again.

You can follow the rest of Rolf Potts’ virtual book tour online, or see him in person at one of 20 cities nationwide as he celebrates the release of Marco Polo Didn’t Go There (Travelers’ Tales, 2008). We encourage you to ask for the book at your favorite local bookstore or Amazon, and follow Rolf’s tour diary at Gadling starting Sept 29th. Tomorrow’s virtual book tour stop will be at The Lost Girls. To read yesterday’s tour stop, go to BootsnAll.com.